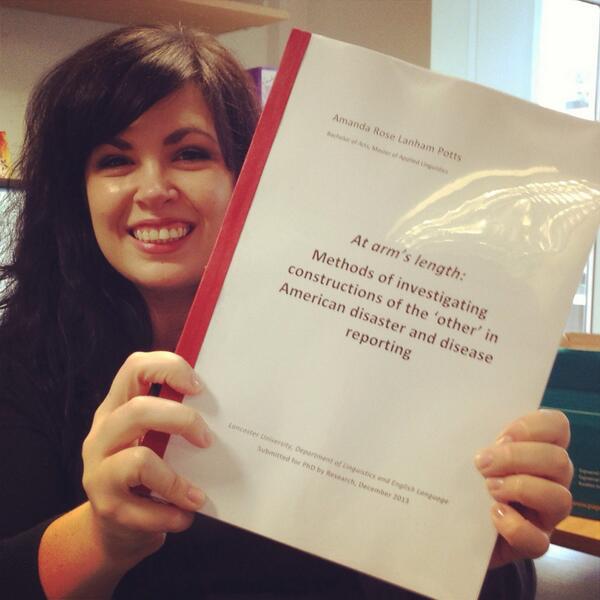

In December 2013, after three years and two months of work, I submitted my PhD thesis. Last month, I successfully defended it, and made the (typographical) corrections in two nights. I’m a Doctor! It’s still exciting to say.

A PhD is certainly not easy — I’ve heard it compared to giving birth, starting and ending a relationship, riding a rollercoaster, making a lonely journey, and more. I relocated across the world from Australia to begin mine, and the start was marked by the sadness of a death in the family. It’s been a whirlwind ever since; throughout the course of my degree, I taught as much as possible, I researched and published outside the scope of my PhD, and in April 2013, I began full-time work in the ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science.

A PhD is certainly not easy — I’ve heard it compared to giving birth, starting and ending a relationship, riding a rollercoaster, making a lonely journey, and more. I relocated across the world from Australia to begin mine, and the start was marked by the sadness of a death in the family. It’s been a whirlwind ever since; throughout the course of my degree, I taught as much as possible, I researched and published outside the scope of my PhD, and in April 2013, I began full-time work in the ESRC Centre for Corpus Approaches to Social Science.

The question that I get most often is a question that I found myself asking for years: how? How do you do a PhD? How do you choose a programme and keep from looking back? How do you keep close to the minimum submission date (or at least keep from going beyond the maximum submission date)? How do you balance work and study? I’d like to share a short series (in three installments) about my degree and my lessons learned. There are many resources out there for people doing PhDs, but I wasn’t able to find any that described my experience. I hope that this might help some others who are [metaphorical representation of your choice] a PhD. Before beginning, I’d just like to stress that these resonate with my personal experience (and with those of many of my friends), but won’t align with everyone’s circumstances.

The first installment is five pointers about what to do when applying to a programme.

1. Have a grasp of what you would like to study. At first, this might be a few paragraphs about what sort of question you’d like to answer, what kind of data you’d like to use, and the sorts of theories and methods you’d like to use. As time goes on, develop this into a succinct two-page document detailing your research questions, expected outcomes, anticipated hurdles, and possible contributions to the field. Of course you can’t detail all of your conclusions (that’s what the 3-4 PhD years are for!) but there are three points to having this document: organising your thoughts and helping you to spot any possible issues; building an argument showing that your work is interesting and promising; demonstrating that you understand how research is structured, have an awareness of literature/theories/methods in your field, understand your limitations, and can convey your ideas clearly.

Something that shouldn’t go into the document but should be kept in the back of your mind as you compose should be this question: How much of this am I willing to compromise on? You will inevitably be challenged about your research goals or position, or questioned about why you have chosen a particular data set or method. I heard a rumour that one reviewer in the department commented on my research proposal: “Is trying to do 3 PhDs”. This person was right; I had proposed three large and dissonant data sets, and I wanted to make both methodological and analytical contributions. Throughout my PhD, I was challenged on this, and I decided to drop one data set (in my case, a corpus), but held strong with the remaining two. It’s very important to understand just how much of your research you’re willing to put aside for later, and how much is critical to your pursuing the degree.

2. Aim to work with a person, not a campus. This likely comes from my experience in American academia, but I believe strongly in the concept of the PhD as an apprenticeship. In order for this to work, you need to have the best possible relationship with your mentors, whether this be a supervisor or a team of researchers. While it’s easy to get charmed by the bright lights of universities in big cities or the prestige of a 500-year-old programme, ultimately, beautiful stone buildings can’t answer your panicky emails and you will be relying on actual people to help you through the PhD.

When you’re devising your research plan, certain ‘names’ in the field will keep cropping up. Do some research on these people; see if they are still in academia. If so, nearly all scholars will have a university website stating whether or not they are taking PhD students and detailing the sort of theses that they have an interest in supervising. They might also have a list of the most recent PhDs that they supervised to completion. You might prefer to have a supervisor who is more experienced, but might not be able to devote as much time to your particular study. Or you might prefer to have a supervisor who is relatively new in the field, but can really dedicate themselves to helping you. This is a matter of personal preference, but it’s a choice that you should give some thought to.

I put together a list of four people who I felt could really contribute to my work and who were located in places that I could see myself living in. Then I emailed these people directly, outlining (briefly) my idea for the study in the body of the email, and attaching the longer research proposal document (#1 above) for their perusal, should they have wanted more information. I asked whether they might be willing, should my application be accepted, to be my primary supervisor. This was an incredibly helpful step, and many people in the UK skip it! I would have known right away whether the person I wanted to study with was unavailable, or not interested in my work. This didn’t happen in my case, but it could have. What did happen was that each person came back to me with some very interesting feedback on my research proposal. Already, I was being guided by experts in my field! It was very exciting, and also gave me a further insight into what it would be like to work with each of them for an additional 3-4 years. Using the advice gleaned from them helped me to polish my research proposal and streamline it to each university I applied to, helping me to achieve acceptance at each of the four institutions, including my top choice: working with Paul Baker at Lancaster University.

3. Have a realistic understanding of finances. This might seem obvious, but PhDs can be very expensive. If you do not have the resources to fully self-fund, do very detailed research on available resources before applying to a specific university. Some people are funded by their home country or institution and can choose from a range of partner universities. Some people are funded by research councils or funding bodies (such as the AHRC or ESRC), and some by faculties or departments. However, each of these options comes with very specific guidelines.

As a non-EU student in the UK, my funding options were extremely limited. I found that many universities here do not offer even a single fee waiver for students of my status, and I didn’t even bother applying to them as I wouldn’t have been able to attend. The best course of action is to survey all of your options very early on. Investigate what is made available by your savings, your family, your home country, and your intended university, faculty, and department. I would strongly recommend against attending a university at which you have not been able to secure funding in the first year, in the hope that funds will be made available in the second year and so on. It’s exponentially more unlikely to receive funding year-on-year, and it’s difficult (but not impossible) to support yourself from month to month on part-time teaching once you’ve arrived. I’ve seen people have to suspend and leave their PhDs due to financial circumstances and it’s heartbreaking. That being said, do get in touch with the administrator for your chosen department or faculty to make sure that you haven’t overlooked something. Your prospective supervisor might also know of possible funding routes, though this can’t be guaranteed.

4. Consider alternative routes. Many universities offer alternative routes to study, including thesis and coursework, part-time study, distance degrees, and online learning. If you don’t have a Masters degree in a field similar to your proposed PhD study, you might consider thesis and coursework, which gives you the chance to mix traditional classroom study with independent research. Students with other commitments (children, full-time jobs, people to care for, etc.) might find that part-time study is the best fit for them. If you live far away from the best university in the world for your degree, a distance or online course will allow you to take advantage of top resources without relocating.

I chose full-time residential PhD by research only, as I have a Masters in Applied Linguistics, I wanted to finish as quickly as possible, and I was in a position to relocate to the UK. Being at Lancaster has given me much greater access to available resources (from the library to the various scholars both working here and visiting), and this has been invaluable. Of course, this isn’t for everyone. But if you’re able to study in residence, do it. If you’re not, make sure to spend at least some time (particularly at the beginning of your degree) at your university. If nothing else, this will give you the valuable opportunity to network with your peers, who become a major support system throughout your entire PhD.

5. Be prepared to sacrifice. Even if all of the stars align — you write the perfect research proposal and get to study what you want, your dream supervisor accepts you at the best university in the world for what you do, you get enough funding to get by — there will still be sacrifices. Being a PhD student means being resource-poor. You will have less time for your loved ones, less disposable income than you might be accustomed to, and less patience for things in your personal life going off track.

As I mentioned in point 1 above, even the most perfectly planned research will ultimately require some pruning as you begin to refine your study, and this is an intellectual sacrifice. Like me, you might be leaving industry to resume studies, and be sacrificing freedoms like comfortable income (financial sacrifice) and unadulterated time off (social sacrifice). The life of a PhD student is one of always working on the thesis, or feeling as though you could or should be working on your thesis. I’ve had friends pause mid-conversation to make notes in the pub on an interesting metaphor or turn of phrase that just cropped up. You never really switch off, which is both exciting and exhausting.

This isn’t completely personal, either. Those closest to you will also have to sacrifice because of your restricted time and finances. You might miss your best friend’s wedding (I did), and you might feel as though others are advancing while you stand still for 3-4 years. Luckily, these sacrifices do pay off; there is a large jump forward at the end, and a huge achievement that those closest to you feel that they can share in. It’s been humbling to see just how far I can push myself and how quickly others will run to meet me. There is also a post-Spartan reward system built into this; now that it’s done and the austerity has been somewhat lifted, I feel a renewed appreciation for simple things like a couple of hours spent watching a horrible movie! What a luxurious treat!

Come back soon for more installments. In Part 2 of this series, I’ll talk about best practices for structuring your work, managing your relationship with your supervisor, and my experience with teaching undergraduates. In Part 3, I’ll discuss the final year(s) of the PhD, with an emphasis on fine-tuning the thesis and preparing for the viva.