Over the past fortnight, various broadsheets and media outlets (see bibliography) picked up the story of my recent article, ‘“Uh…..not to be nitpicky,,,,,but…the past tense of drag is dragged, not drug.”: An overview of trolling strategies‘ (2013), which came out in the Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict. Of the thousands of comments collectively posted on those articles, one particularly interesting point that came through (out of many) was the general sense that there exists a single, fixed, canonical definition of the word troll which I ought to be using and had somehow missed.

So what is the definition of troll? In my thesis, I spent a rather lengthy 18,127 words trying to answer precisely this question, and very early on I realised that trying to discover, or, if one didn’t exist, to create a clean, robust, working definition that everyone would agree with would be close to impossible. There are at least three major problems, which for simplicity’s sake are best referred to as history, agreement, and change.

History

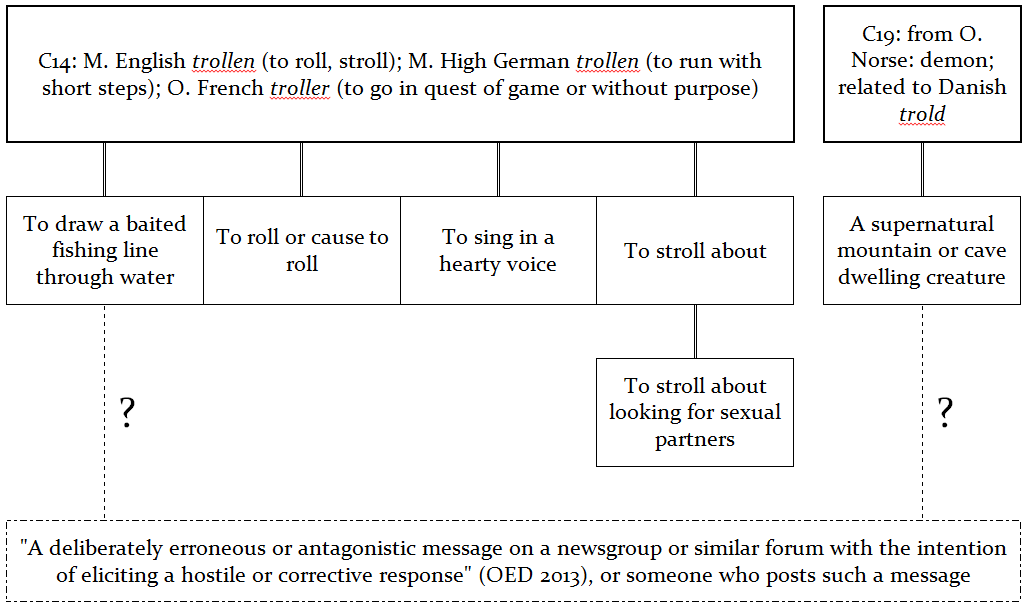

Firstly, it’s important to distinguish between a word and that word’s separate meanings (e.g. the word ring can mean a doorbell sound, an item of jewellery, etc.). When we look at the word troll, we find that it has quite a few meanings related to angling, rolling, walking, singing, and of course, online misbehaviour. However, whilst there are suggested etymologies for the angling, rolling, walking, and singing senses, it isn’t clear which of these meanings than gave rise to the newer “online misbehaviour” meaning that we now use:

So since an etymological investigation doesn’t get us very far, the next step is a classic linguistic approach of observing how ordinary people use the word troll…

Agreement

Broadly speaking, there are two ways to look at how a word is used. We can look indirectly, by checking dictionaries. (Note that dictionaries are records of word-usage, not mandates on how they should be used!)

troll, v.

intr. Computing slang. To post a deliberately erroneous or antagonistic message on a newsgroup or similar forum with the intention of eliciting a hostile or corrective response. Also trans.: to elicit such a response from (a person); to post messages of this type to (a newsgroup, etc.). (OED 2013: draft additions March 2006)

We can look directly at how users use and define the word:

“The aim of the troll is to change the subject.” (Guardian 2013: Toeparty)

“Trolling (trying to derail, intimidate or get a thread closed down) might be part of an astroturfing campaign, but not the other way round.” (Guardian 2013: callaspodeaspode)

A In a blatant attempt to blast my way to the top of the charts all over [newsgroup] I am going to start this completely pointless thread. [SF050806]

B So basically you have become a troll. [SF050806 (cont.)]

C No, a few people want to see him face due process for something that *you* see as trollign and others see as racial hatred and homophobia. [SF060707]

D Now, after a year or so, I have finally witnessed some troll posts. Not just nasty, abusive and anonymous, like E’s, but hostile imitations of other NG users, intended to increase the sum of NG unhappiness – which in my view is quite high enough without their help.. [RE070210]

F Your comments, all too often, come with only invective and insult and contain no content whatsoever. This latter is well within the definition of trolling and baiting. [RE051015]

And there is also a third approach that combines the former two – the crowd-sourced dictionary. This is a dictionary whose entries are submitted, and voted on, by ordinary users:

troll, n. (13,319 up-votes, 2,699 down-votes)

One who posts a deliberately provocative message to a newsgroup or message board with the intention of causing maximum disruption and argument. (Urban Dictionary 2013)

A brief glance over the above three sources, however, reveals a fairly clear problem, summarised as “two people, three opinions”. In different words, however self-evident A’s definition may seem to A, we need only ask B to find that s/he has an equally self-evident, yet different definition. Likewise, our findings demonstrate that troll is being used to cover a range of behaviours from the dictionary-favoured broad notions of general provocation and antagonism through to user-favoured specific strategies including changing the subject; posting pointless content; being insulting, abusive, and nasty; and even being hateful and homophobic. However, none of these definitions are one-offs. Each is repeated dozens, or even hundreds of times in varying guises across different sites and by different users. So, if the meaning of troll is apparently so obvious, why is there this much disagreement?

The problem is that whilst certain words are predisposed to produce clear cut, well-agreed-upon definitions (e.g. “car”, “table”), others can be far more subjective (e.g. “patriotism”, “dishonesty”). This leads to users developing their own particular understanding of what that word means. Further, new words and meanings may go through a period of semantic instability, whilst the users of that word settle on a generally accepted definition. This instability can be increased by the ways that public figures and media outlets choose to interpret and employ a word, particularly if it is from a fashionable or sensational field. This can lead to uses that are contradictory, hyperbolic, and inconsistent, yet at the same time, these very same uses are also likely to shape the audience’s understanding.

Overall, then, newness and subjectivity can be a recipe for wide disagreement between users about exactly what a word can, does, or should mean. This leaves the linguist in the awkward position of trying to decide, “Well, whose definition do I pick? Who gets the honour of ‘owning’ the term and defining it? What even gives me the right to make that decision?” Unsurprisingly, many researchers will be deeply dissatisfied with the idea of lottery-picking a random definition out of many and simply crowning that the final definition. One solution, then, might be to go back to the oldest, clearest definition of troll that we can find that relates to online behaviour, and use that to set the standard. But even this is not without its problems, and this takes us neatly into language change…

Language change

For many laypeople, the idea of language change is inextricably tied up with worries about language decay or debasement. In reality, however, language change is not only inevitable, it is vital. Shedding old words or meanings, and acquiring new ones is essential if a language is to stay healthy and relevant, just as shedding old leaves and growing new ones is essential for a tree to continue flourishing. Both languages and trees that fail or “refuse” to do this run the risk of dying. One way for a word to avoid being shed is to evolve – to take on new meanings, or to allow existing meanings to change. For instance, we need only look at the history of the word nice to see that over time, its meanings have ranged from “silly/foolish” to “precise” to “commendable”. But what records do we have of the earliest usages of troll?

One good place to start is Usenet, the alleged origin of the term (though we have no hard evidence to back this claim up). If we go back to the early 1980s, however, whilst Usenet existed then, we are working with incomplete data, since the expense and limitations of storage at the time meant that an indeterminate amount of content was never stored at all, only stored for short periods, or has since been lost. When looking throughout 1980s Usenet posts, I also couldn’t find any really good, clear-cut examples of troll being used to mean online mischief-making, or anything close to it, from the 1980s. There are ambiguous, debatable examples, e.g. Mauney (1982), Maddox (1989) and Miller (1990), but I’d suggest that the best I’ve found so far is this:

Remember that people come here for help, often. There may also be those who can’t believe there can be a flame-free group on the net. Or even those who see a lack of flaming as a weakness. Or, perhaps, those like the troll in Gilly’s story (metaphorically speaking), who want to start a flame war and step back to watch the chaos. (Doyle 1989)

Even in this case, though, is troll being used in anything related to the current sense? Or is it a purely coincidental allusion? Once we move into the 1990s, the number of examples increases dramatically, but already, differences in the term are becoming more widespread, and if we are to believe the individuals who claim that they were using the term in the 1970s, then by the 1990s this word is already well over a decade old, allowing plenty of time for a proliferation of different meanings.

To return to the issue of language change, “trendy” terminology associated with fast-moving fields like science and technology tends to change especially quickly. At the same time, technology has evolved almost beyond recognition since the 1970s, and computers are no longer the preserve of the wealthy universities and their PhDs in Computer Science. Instead, in some parts of the world, computers are simply ubiquitous, and they are being used by an unprecedented number of new users, who have brought with them an entire spectrum of new expectations, needs, wants, and behaviours. With all this in mind, even if we could find a clear, robust, dictionary-worthy definition of troll from the 1970s, it is no more likely to perfectly fit today’s usage as the very best IT from the 1970s will still be cutting-edge now.

So… how do we define troll then…?

How do we resolve these history, agreement, and language change problems? There is more than one solution to this problem, but mine was to use a lot of online data – 80 million words, in fact. From this, I extracted all the instances of trolling that I could find, and identified the consistent, major themes that users referred to as being a part of trolling. Once I had those themes, I amalgamated from them a generic, umbrella definition of troll. Crucially, this isn’t typically based on how (alleged) trolls themselves use the term. In the data, loosely speaking, for every 1,000 examples of individuals talking about trolling (e.g. discussing whether they are being trolled, whether A is a troll, whether a certain behaviour counts as trolling) there was roughly only one example of a (supposed) troll – accused or actual – discussing their own intention to, or success at trolling. In other words, my definition of trolling is actually heavily – in my view too heavily – built on interpretation, rather than intention. However that may be, the final definition that I came to, as it currently stands is that trolling is…

the deliberate (perceived) use of impoliteness/aggression, deception and/or manipulation in CMC to create a context conducive to triggering or antagonising conflict, typically for amusement’s sake. (Hardaker 2013: 78)

Once I had established this deliberately broad definition, I set about identifying some of the consistent sub-themes, which I then published in my 2013 paper. As it turns out, identifying every trolling strategy is a task that could take up many lifetimes. Given the size of the internet, even an 80 million word corpus is a drop in the ocean of all published online text, so the few methods that I found are very unlikely to be all the types that exist. However, because of the proliferation of subtypes that began to emerge, I also quickly decided against giving each specific troll-like behaviour its own particular name (e.g. griefer, etc.) since this seemed much more likely to increase confusion that reduce it.

Conclusion

Overall, each individual is likely to have their own understanding of what troll means, and inevitably, any one person’s definition, whether academic or personal, is unlikely to fully agree with at least one other’s. Some defend their definition because they’ve been using it for a long time, because it’s the one that they and all their friends or colleagues use, and/or because they feel that theirs most accurately represents what they see online. And as far as I am concerned, every one of these reasons is perfectly valid. However, whilst each individual has a right to their own definition, no one individual can claim to own the definition. Likewise, just because my definition is built from thousands of examples, that isn’t the crowning, final word on the matter either. For a start, it was derived from a particular subset (80 millions words) of a particular part of the internet (Usenet) from a particular timeframe (2005-2010), so any results drawn from that data must be subject to future refinements, since newer, older, different, or more data will likely bring new insights that my definition cannot account for. Also, within only a short time, my original dataset, and any results taken from it, will start going out of date. The only solution to this is newer data from a wider range of sites.

In a nutshell, comprehensively defining even one meaning of one word is a never-ending task, and however well-researched a given definition at the conclusion of that project, it is still highly unlikely that every user will agree with it. Added to that, the newer the word or meaning, the more abstract or “trendy” it is, and the more quixotic the field it belongs to, the wider the differences between individual definitions are ultimately likely to be.

Bibliography

Doyle, Jennifer (1989). Re: <hick!>. alt.callahans. December 14. https://groups.google.com/d/msg/alt.callahans/SphfCkUsdtY/FggkP4rvoQEJ.

Hardaker, Claire (2013). “Uh…..not to be nitpicky,,,,,but…the past tense of drag is dragged, not drug.”: An overview of trolling strategies. Journal of Language Aggression and Conflict 1(1), 57-85.

Maddox, Thomas (1989). Re: Cyberspace Conference. alt.cyberpunk. October 22. https://groups.google.com/d/msg/alt.cyberpunk/976Vj9FPX3Q/3Ytxg-JeCdMJ.

Mauney, Jon (1982). second verse, same as the first. net.nlang. July 05. https://groups.google.com/d/msg/net.nlang/YNX8PlANL_g/Uveya3fB1ZkJ.

Miller, Mark (1990). FOADTAD. alt.flame. February 08. https://groups.google.com/forum/?fromgroups=#!msg/alt.flame/RMlMz6ft4r8/SwPcwihXE4AJ.

OED (2013). Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press: http://dictionary.oed.com.

National media

Ahmed, Murad (2013) The devil makes work for online trolls’ idle hands. The Times. June 28.

Griffiths, Sarah (2013) Boredom is to blame for most cyberbullying incidents, claims expert who’s identified the key tactics of trolls. Daily Mail. June 27.

Hardaker, Claire (2013) Internet trolls: a guide to the different flavours. Guardian. July 01.

Krotoski, Aleks, Jason Phipps, Charles Arthur & Jemima Kiss (2013) Tech Weekly Podcast: Understanding the internet troll. Guardian. July 10.

Mackie, Bella (2013) Guardian Comment of the week: a closer look at internet trolls. Guardian. July 04.

Sanghani, Radhika (2013) Top reasons for trolling include boredom and amusement. The Telegraph. June 27.

Sherwin, Adam (2013) Trolls who post vicious abuse on Twitter aren’t acting out of malice – they’re just bored, reveals study. Independent. June 27.

The Telegraph (2013) Online trolls post abuse out of boredom, research finds. The Telegraph. June 27.

International media

Ahmed, Murad (2013) Society: Idle hands, devil’s work. The Australian. July 13. [Australia]

Independent. Boredom main cause of internet trolling – survey. Independent. June 28. [Ireland]

Istiliyanova, Nikol (2013) Клеър Хардакър: Платеният от партии интернет трол е лицемер. Dnevnik. July 08. [Bulgaria]

Joop (2013) Trollen doen het vooral uit verveling. Joop. 27 June. [The Netherlands]

Malaysia Sun. Boredom main cause of internet trolling – survey. Malaysia Sun. June 28. [Malaysia]

Maquoi, Evi (2013) Pesterijen op Facebook en Twitter nemen toe door verveling. ZDNet. July 01. [Belgium]

Sáu, Thứ. 7 chiến lược “troll” hữu hiệu. Vietnam Review. 28 Jun. [Vietnam]

The Telegram (2013) Cheers & Jeers. The Telegram. July 08. [Canada]

Times of India. Boredom drives trolls on Facebook and Twitter. Times of India. July 01. [India]