Have you noticed that academic writing in books and journals seems less formal than it used to? Preliminary data from the Written BNC2014 shows that you may be right!

Some early data from the academic journals and academic books sections of the new corpus has been analysed to find out whether academic writing has become more colloquial since the 1990s. Colloquialisation is “a tendency for features of the conversational spoken language to infiltrate and spread in the written language” (Leech, 2002: 72). The colloquialisation of language can make messages more easily understood by the general public because, whilst not everybody is familiar with the specifics of academic language, everyone is familiar with spoken language. In order to investigate the colloquialisation of academic writing, the frequencies of several linguistic features which have been associated with colloquialisation were compared in academic writing in the BNC1994 and the BNC2014.

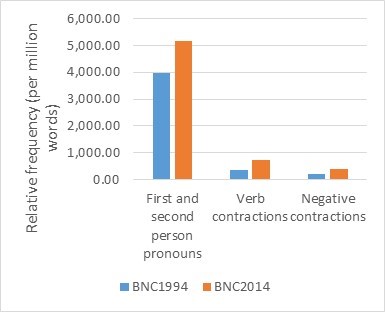

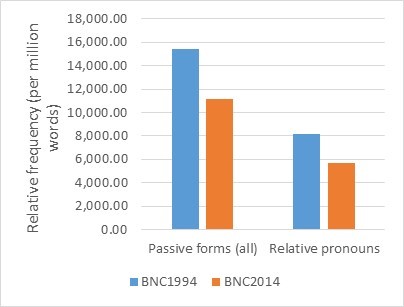

Results show that, of the eleven features studied, five features have shown large changes in frequency between the BNC1994 and the BNC2014, pointing to the colloquialisation of academic writing. The use of first and second person pronouns, verb contractions, and negative contractions have previously been found to be strongly associated with spoken language. These features have all increased in academic language between 1994 and 2014. Passive constructions and relative pronouns have previously been found to be strongly associated with written language, and are not often used in spoken language. This analysis shows that both of these features have decreased in frequency in academic language in the BNC2014.

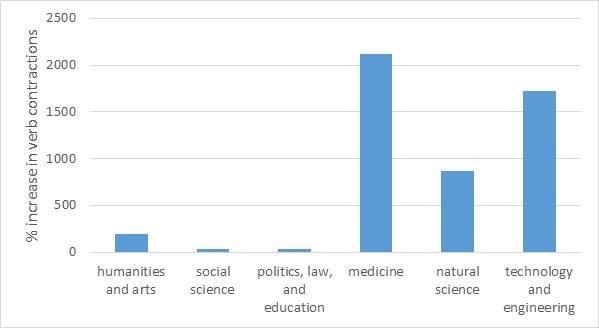

These frequency changes were also compared for each genre of academic writing separately. The genres studied were: humanities & arts, social science, politics, law & education, medicine, natural science, and technology & engineering. An interesting difference between some of these genres emerged. It seems that the ‘hard’ sciences (medicine, natural science, and technology & engineering) have shown much larger changes in some of the linguistic features studied than the other genres have. For example, figure 3 shows the difference in the percentage increase of verb contractions for each genre, and clearly shows a difference between the ‘hard’ sciences and the social sciences and humanities subjects.

Figure 3: % increases in the frequency of the use of verb contractions between 1994 and 2014 for each genre of academic writing.

This may lead you to think that medicine, natural science, and technology & engineering writing has become more colloquial than the other genres, but this is in fact not the case. Looking more closely at the data shows us that these ‘hard’ science genres were actually much less colloquial than the other genres in the 1990s, and that the large change seen here is actually a symptom of all genres becoming more similar in their use of these features. In other words, some genres have not become more colloquial than others, they have simply had to change more in order for all of the genres to become more alike.

So it seems from this analysis that, in some respects at least, academic language has certainly become more colloquial since the 1990s. The following is a typical example of academic writing in the 1990s, taken from a sample of a natural sciences book in the BNC1994. It shows avoidance of using first or second person pronouns and contractions (which have increased in use in the BNC2014), and shows use of a passive construction (the use of which has decreased in the BNC2014).

Experimentally one cannot set up just this configuration because of the difficulty in imposing constant concentration boundary conditions (Section 14.3). In general, the most readily practicable experiments are ones in which an initial density distribution is set up and there is then some evolution of the configuration during the course of the experiment.

It is much more common nowadays to see examples such as the following, taken from an academic natural sciences book in the BNC2014. This example contains active sentence constructions, first person pronouns, verb contractions, negative contractions, and a question.

No doubt people might object in further ways, but in the end nearly all these replies boil down to the first one I discussed above. I’d like to return to it and ponder a somewhat more aggressive version, one that might reveal the stakes of this discussion even more clearly. Very well, someone might say. Not reproducing may make sense for most people, but my partner and I are well – educated, well – off, and capable of protecting our children from whatever happens down the road. Why shouldn’t we have children if we want to?

It will certainly be interesting to see if this trend of colloquialisation can be seen in other genres of writing in the BNC2014!

Would you like to contribute to the Written BNC2014?

We are looking for native speakers of British English to submit their student essays, emails, and Facebook and Whatsapp messages for inclusion in the corpus! To find out more, and to get involved click here. All contributors will be fully credited in the corpus documentation.