After submitting and successfully defending my thesis a few months ago, I’ve decided to share some ‘lessons learnt’ over the course of my 38 months as a PhD student.

In Part 2 of this series, I’ll talk about best practices for structuring your work, managing your relationship with your supervisor, and my experience with teaching undergraduates. If you missed “Part 1: Preparing for the programme”, you can read it here.

Structuring your work

I believe it’s healthy to treat your PhD—as much as possible—like a job. Like any job, a PhD has physical, social, and temporal boundaries.

Try to create a PhD ‘space’. Make use of your office if you’ve been given one at your university, and create a space within your home that is a ‘work area’ if you haven’t been given one. Working from bed, from the sofa, or from a café means that your PhD is infiltrating all areas of your life. While some degree of this is inevitable, it’s best to keep physical boundaries as much as possible, even if you can only keep it to your desk.

By the same token, making friends outside of your department or your field is helpful in many ways. I adore my friends from Linguistics and I couldn’t have finished my doctorate without them, but you wouldn’t solely hang out with friends from work when you’re at home, and this is the same situation. In a group of people who have a similar background, you might end up talking about your field ‘outside of hours’. This can be stimulating, but also exhausting. You may want to vent about your department, or talk about something other than your PhD or field, even trashy TV! It’s easier with friends from other areas. As a nice extra feature, the connections that you make outside of your field can also help you inside your field. I’ve had very good advice from friends working in statistics, gotten ideas from historians, and been inspired by literary scholars, even though I might never venture into these areas in the library.

If you can, also create a routine for yourself, even if this isn’t 9-5. It’s best if this routine involves physically moving locations, but even if it doesn’t, physically change something: take a shower, get dressed for work. Pick 8 hours within the day that you work best, and work during those hours. Don’t be too hard on yourself if you have a short day or miss days out entirely…a PhD is ‘swings and roundabouts’ as they say around here…it’s long enough that you will make up the time to yourself. As much as possible, take the weekends and holidays off. This might mean working longer than 8 hours on weekdays, but personally, I think it’s worth it. Many people study in a place far from where they grew up, and a PhD is one time in life where you can be flexible enough with your time to enjoy a bit of sightseeing and tourism.

During this routine, set clear goals for yourself. I’ve seen people arguing for and against writing something every day. I found it very helpful to set a daily word count goal for myself, then sit in front of a computer until I at least came close. The number isn’t important: at the start of my PhD, I aimed to write 200 words per day; at the end of my PhD, I was able to write 1,000 words per day. What is important is getting into a routine. You will sit down some days and feel horrible. You’ll have writer’s block. You will struggle through each word of those 200, and know that you’ll delete most of them. But it’s much easier to get 40 great words out of 200 bad ones than to write 40 words completely cold. I’ve written entire chapters three times as long as they needed to be, and hated them. But paring them down is cathartic—it’s like sculpting. The bonus is that when you get into the habit of writing every day, you slowly get into the habit of writing something good every day. Soon, you’ll be writing 100 words and keeping 50 of them. Then you’ll be writing 1,000 words and keeping 900 of them. The important part is keeping the pace: just write! Your supervisor will also appreciate having something tangible to mark your progress (see next section).

As far as the structure of my own work, there are three things that I would do differently, if I could do it all again:

- Decide on a reference manager and stick to it diligently from Day 1. At the start of my degree I used EndNote for reference management, as this was offered for free by my university and came in both desktop and web versions. For my whole first year, I used EndNote to create an annotated bibliography—an extremely useful tool when drafting your literature review. However, EndNote began crashing on me, and papers were no longer available. In my second year, I stopped keeping track of references and just kept haphazard folders of PDFs. In my third year, I just used in-line citations, believing that sources would be easy to find later on. Not true! The month before submission I decided to make the leap to Mendeley, a truly amazing (free) reference manager that allows you to build and share libraries, store your PDFs, search other people’s collections, and select from a vast array of output styles (I favour APA 6th edition). The transition was extraordinarily painful. Exporting from Endnote was problematic and buggy, scanning PDFs in Mendeley was error-prone, and finding the corresponding works for those in-line references was impossible in some cases. I wasted a solid week just before submission sorting out my references, and this really should have been done all along. It would have been so painless!

- Master MS Word early on. In my final year, I finally got serious about standardising the numbering of my tables and figures, which means that in the eleventh hour, I was still panicking, trying to make sure that I had updated everything to the proper styles and made appropriate in-line references to my data. Had I set my styles earlier on and made the best use of MS Word’s quite intuitive counting and cross-referencing mechanisms, I would have saved myself days of close reading. If you are using MS Word (sorry, I can’t say anything about LaTeX) and you are not using the citation manager or cross-reference tool, learn how to do that immediately. Today. Your library might have a class on it, or, like me, you can brush up in an hour of web searching.

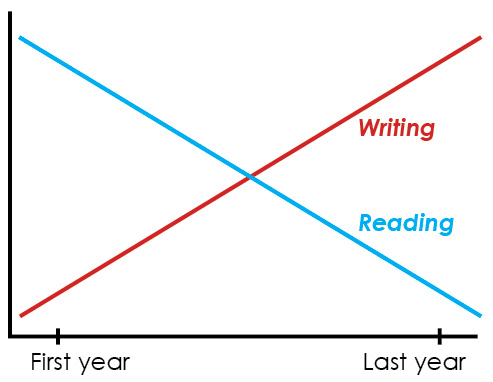

- Put down the books earlier. At a certain point, you need to generate new research and make a novel contribution to knowledge. Your first year and much of your second year will be dedicated to making sure that a research gap exists, and that you can pay tribute to all of the giants whose shoulders you will be standing on. However, burying yourself in a library for three years reading everyone else’s great works is a good way to paralyse yourself. Of course you will always need to keep up with the times, but a certain point, your rate of writing will overtake your rate of reading. If I could do it again, I would follow a pattern more like this:

After the first year, you won’t be missing anything totally fundamental. After the second year, you won’t be missing anything peripheral. If, in the third year, you’ve missed something very fresh, your examiners will point it out. But the more important thing is to make a contribution. Most of the PhD is research, not literature review. Your supervisor will be able to help you with this, and with other things (but not really others), as I discuss below.

Managing your relationship with your supervisor

As I said in my previous post, the best thing that you can do to kickstart your relationship with your supervisor is to be in touch with them before you begin. Start the collaboration early by running your research proposal by them. Some supervisors might even request an informal phone call (mine did) or a formal phone interview (mine didn’t); this is a great opportunity to see how you might get on.

Like me, you might get incredibly lucky with your supervisor. Like some of my friends, you might get not-so-lucky. Circumstances of unluckiness run the gamut: your supervisor might be a) very busy and not have much time to dedicate to mentoring you; b) too far outside of your field to give hands-on help, even if they’d really love to be able to; c) not the best fit for any of a number of reasons – they might have something major going on in their own life (Supervisors are human! Amazing!) , or your personalities might just not gel. You might have more than one supervisor, compounding these possibilities. In any event, lucky or unlucky, I think the most important thing to remember is that it’s not personal.

For you, your PhD is special; it’s one of the most important things that you’re doing, if not the most important. But it’s also just work – for you, and certainly for your supervisor. It’s easy to get caught up in insecurity, feeling that you’re maybe floundering and people aren’t helping you as much as you’d like, because they don’t like you or don’t think you’re worth it. I can guarantee that this is not the case, because it’s not personal. The administrators, lecturers, and professors in your department are all juggling their research, teaching, and admin, and they’re all going home to family and friends and doing some more juggling. Something that my supervisor is very good at, and that I’m trying to get better at, is keeping it professional.

If something in your personal life (mental/physical health issues, problems with relationships/family/children) is getting in the way of your PhD, by all means, 100%, definitely, indubitably, talk to someone about it. This might be your supervisor, your department administrator, your faculty officer, or a counselor. However, in almost all scenarios, your supervisor is a better adviser for academic (professional) matters. You chose them as a master in their field, so it’s best to use your time with them to ask things like: Can you see any flaws in this study design that I’ve missed? Does this chapter structure flow well to you? Is there a source that you can recommend that can help me to define/grapple with something tricky?

As time goes on in your PhD, your relationship with your supervisor(s) will also necessarily change. In your first year, you rely a lot upon them, as you are very much an apprentice. The experience is very new, and for most of us, this is the first and only time we’ll ever write a PhD thesis. In my first year, I followed the pace suggested by my own supervisor, and I made alterations that were (gently) suggested by him. By your second year, you will become more independent. Your supervisor’s influence in your work will become less apparent, and you won’t be receiving as much explicit instruction. During this time, they can help you with broad problem areas, such as: data collection, method design, writing structure, etc. I think it’s important to note that you can also only get out what you put in. If you do not give your supervisor any (written) work to review, then you are not making the most of the arrangement. It’s best practice in the second year to come to every meeting with something new to discuss, whether this be a new chapter section, some new results, or a new data set. By the time you are in your third and/or final year, you will be more expert in your narrow field of inquiry than your supervisor. At this point, the best thing for you to do is to practice independence. Set your own deadlines and agree these with your supervisor, then stick to them. While your supervisor will make suggestions, you should be critical of your own work and decide on your own whether incorporating these changes, leaving the piece unchanged, or going for a third method will make it most defensible. In the UK (and I believe many other countries), your supervisor is not able to speak during your viva, so it’s critical that you fully understand the implications of making late-stage changes and can adequately justify these both in the thesis and in person, should the matter come up. A good PhD is a great apprenticeship, and at the end, you should feel fully comfortable in yourself as a practitioner. If, at the end of the experience, you still felt as though you had to double-check with somebody else about every change, this would be a failure in the system. So go forth, confidently!

Teaching undergraduates

I’ll end this blog post with a discussion about PhD students’ opportunity to take up a mentorship role themselves: teaching. I should start this section by saying that I am a firm supporter of teaching while doing a PhD. Some people decide not to teach as they believe this will distract them from their main goal, and of course, that’s a personal decision. However, looking back now, I believe that teaching is one of the most enriching experiences that can be layered upon a PhD.

First, there are financial benefits. Part-time teaching is a large proportion of many PhD students’ personal finances, and can be particularly crucial for those who are self-funding. Though most universities will say that it is incredibly difficult to support yourself as a part-time teacher, I was able to do so on a mixture of part-time teaching and whatever else came up (working in the library, event planning, teaching English in the summer, etc.), albeit quite leanly at times. For students who are not funded with stipends, this is a very valid way of making up a proportion of living costs.

Then there are ‘contact’ benefits. Interacting with undergraduates is incredibly refreshing—they are curious and energetic, and they ask questions which make you think creatively. When you are challenged to describe your own field and forced to answer for someone who is a novice or just learning about your sub-discipline, you become much more clear and concise in the way that you describe your area. Though many questions or comments might be completely off the wall, some will really make you think. Most people who undertake a PhD will have been at the top of our classes, be very driven, and have found what we’re intrigued by. I struggled to understand when a student told me (at another university) “C’s get degrees”, because I would have been devastated to receive a C. However, I have seen a student at the verge of failing be absolutely chuffed to have earned their C. It’s important to come into contact with people who aren’t exactly like you, and to understand what drives them and what inspired them to pursue a higher education. This makes us better educators. Lancaster University has a huge linguistics programme at every level, but statistically, not many of my students will go on to be linguists. I love talking to them about what they plan to use their linguistic ‘tool kits’ for. Many will be teachers; some will be journalists, marketing or advertising agents, designers, writers, translators. Thinking about how they will apply the tools and techniques I show them makes me think about the novel ways that I could apply them. The reason that I found myself at CASS is because, like everyone else at this centre, I strongly believe that research should find its way out of the ivory tower and into real-world application. Often, students inform us how we could do this best. Like me, you may meet some particularly bright or funny students, or you might meet a student at a point in their life where they need help, and you might be able to offer them that. You can give advice on their own dissertations, funding applications, job prospects, and you can make a real difference for some students. Some of them will write you cards or write you into their acknowledgements, or write you emails a year or so after graduation. Having this kind of contact makes me more empathetic in general, and keeps me grounded in my own reasons for undertaking a higher degree.

Finally—and I think that this is a major consideration for all PhD students who would like to continue on in academia—there are CV benefits to teaching undergraduates. Nearly the world over, academia is a saturated market at the moment. Competition for jobs is fierce, and you must try to set yourself apart from other candidates in whatever way you can. Finishing a PhD in time is great, but there will be a hundred others who have just done the same. The best way to place yourself in the job market is to diversify your CV: get experience in teaching, publish papers (or reviews), participate in event organisation. While many people could comfortably miss out on the financial and social benefits of teaching, consciously allowing a black hole in that section of your CV might be the difference between being shortlisted or not. I would recommend taking on at least one or two seminars. See how it goes! If you’re like me, you’ll find it very rewarding.

Check back soon for the last installment of this series. In Part 3, I’ll discuss the final year(s) of the PhD, with an emphasis on fine-tuning the thesis and preparing for the viva.